The history of African music recording and archiving can be seen most clearly and compellingly by detailing the history of a few key individuals, who were pioneers in their field. At the turn of the 20th Century, a colonised Africa was viewed as backward and void of any real culture worth preserving, which is why these ethnomusicologists were not only groundbreaking in their ideas, but revolutionary. They understood, far before the rest of the Western world could even comprehend, that traditional African music – with its complexity of rhythms, flair for storytelling and historical richness – was worth preserving.

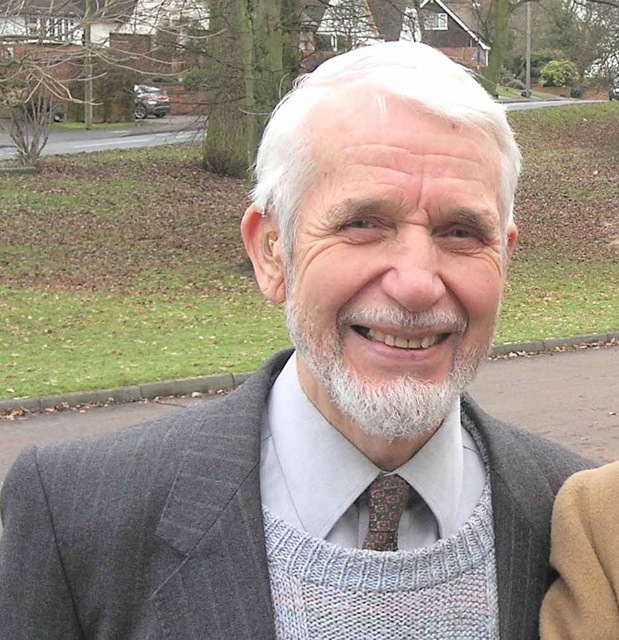

Hugh Tracey 1903 – 1977

Arriving in Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe – in 1921 with his brother, who had been awarded land after his efforts in World War 1, the young man of only 18 years old had the foresight of a wise elder. He was surrounded by disdain for African culture from the Christian missionaries, who forbade the playing of the mbira, due to the pagan themes of ancestor worship and the insurrectional ideas gleaned from spirits that featured heavily in the songs. However, Tracey was able to see past the prejudice and ignorance. He was fascinated by the songs, which were sung by the Shona farmers, with whom he and his brother worked alongside on the tobacco fields. He was said to have been ‘bitten’ by Africa; ‘he got cultural malaria.’ Tracey, although very aware of the colonial oppression of African culture, or perhaps because of it, made it his life mission to record traditional African music; a mission which many others adopted after him. After making the first recording of indigenous Rhodesian music, being awarded the Carnegie Fellowship grant to study South Rhodesian music, with which he made over 600 recordings, and inspiring traditional English musicians, Ralph Vaughn Williams and Gustav Holst, at the Royal Academy of Music, who urged him to “discover every chord” of traditional African music, Tracey ran out of funding. He became a broadcaster, utilising every opportunity to promote African music.

However, he could not stay away from Africa long, and in 1946 realised someone needed to fully dedicate their time to “appraising the social value” of traditional African music, otherwise it would disappear. Tracey would have to step up and be that someone, especially at a time when African radios wanted to broadcast in their own regional vernaculars but had no recordings of regional music to play. He was lucky enough to obtain funding from Eric Gallo, who owned a recording label in South Africa. They had a “gentlemen’s agreement” that any artists Tracey discovered who had commercial potential, he would forward to Gallo. He therefore started the career of some of Africa’s first popular musicians, such as Jean Bosco Mwenda. Masanga, by Mwenda, was one of the first truly popular songs in Africa.

However, as Tracey’s particular concern was that the recordings he made were kept authentic and not manipulated for commercial use, he strayed from the popular African music he was helping to create, and continued to focus more on the traditional. He secured funding from various projects, after a lecturing tour in the UK, and set up The International Library of African music in 1954, where his 20000 recordings are today stored. The ILAM will be explored further in a later blog of this series.

- There are a few of Hugh Tracey’s recordings available online on the British Library Sound Archive, under the David Rycroft South African Collection. However, to play these you need to be studying further or higher education to obtain access to these.

- More Hugh Tracey, his Sounds of Africa and Music of Africa, can be found on the British Library Sound and Moving Image Catalogue – however, this simply confirms the existence of the recording. To listen to the recordings, one must make an appointment with the Listening Service to listen to the recordings on site at the British Library.

- Michael Baird produced 21 CDs of Tracey’s work; Historical Recordings of Hugh Tracey series. These can be bought online at SWP Records and a review of most of the CDs can be found here. Michael Baird said “The sad conclusion after compiling this series is that so much music recorded by HT [Hugh Tracey] has since disappeared — within the space of fifty years. This is something HT foresaw and why he spent most of his life recording this music for posterity. It was not so much Tracey’s ‘knack’ of being at the right place at the right time, but his awareness and vision coupled with organisation and his tremendous energy which give us the opportunity to listen to the many exceptional musicians he recorded today. In this series we are able to present many of the foremost musicians of the 20th century from this part of Africa — and that is a gift. It is especially a gift to the peoples involved, for the legacy as played by their forebears belongs to them.”

- ILAM has reissued, without modifications, on CD, Tracey’s Music of Africa Series

- Several albums can be bought on iTunes

Klaus Wachsmann 1907 – 1984

Wachsmann was a German born English ethnomusicologist, who travelled in Africa in 1937 as a missionary, serving in several offices in the Office of the Protestant Missions in Uganda. He was to do unpaid work with sacred music at Namirembe and with choral school choirs, before being promoted to more senior roles and then he was paid a salary. However, instead of quelling the African music culture – as those missionaries who Hugh Tracey encountered clearly did – Wachsmann lived for 20 years in Uganda working to preserve and archive it. During World War II, according to Peter Cooke in Ethnomusicology in East Africa: Perspectives from Uganda and Beyond, Wachsmann had his camera confiscated because he was regarded as a “friendly enemy alien”. This, coupled with the fact there was no running water at the Museum he was then to work in, explains why there are so few photographic records to go with his 1500 sound records. After his missionary work, he became Curator of the Uganda Museum and while there collected many musical instruments.

He received a grant from the British Government in 1949 – demonstrating that even Government authorities began to realise how essential documenting traditional African music was – which enabled him to record these 1500 recordings with the help of a sound engineer, who was responsible for the fantastic quality of the recordings, which he kept at the Uganda Museum. Wachsmann left Africa, and his tapes, in 1957 and worked in London as the Scientific Officer in charge of Ethnological Collections at the Wellcome Foundation until 1963. It was then that he was invited to become a lecturer at UCLA and was reunited with his tapes at the university, as the Uganda Museum did not have the equipment to archive them adequately. However, disaster struck and the tapes were unfortunately destroyed by a flood of the UCLA basement, demonstrating the difficulties of archiving with an easily destructible medium like reel-to-reel tapes and the importance of now digitising these perishable recordings. The sound engineer who had recorded the music with Wachsmann kindly offered up the copies he had made a kept aside.

Wachsmann went on to lecture at various universities and was awarded the bronze medal for “Devoted Service to Africa” from the Royal African Society in 1958. His legacy lives on as he gives his name to a prize for advanced and critical essays in organology, at The Society of Ethnomusicology. Moreover, the Klaus Wachsmann Music Archive at the Makerere University, Uganda, has recently been set up. There is a course in archiving at the university and archive at UCLA has been collaborating with Makerere University to provide up to date tools and skills, such as the digitisation of DAT and reel-to-reel tape. Dr Sylvia Nannyonga-Tamusuza from the university, in this article, sums up the importance of archiving “My hope is to create materials for secondary schools from the archive. In that way, (students) can be able to remember and to understand what was there before […] With the recordings, we can give (students) some background and some context; they would be able to understand and go find out more by themselves […] My thinking is that a culture that doesn’t have a history is a dead one.”

- His recordings are available to play online, for anyone, in the Klaus Wachsmann Collection at the British Library.

- Copies of his recordings can also be found at the UCLA archive, but cannot be streamed online.

David Fanshawe 1942 – 2010

David Fanshawe recording the Luo Tribe, Kenya, 1973. Photo Judith Croasdell

David Fanshawe did not limit himself to the confines of ethnomusicology and is described as an ‘internationally distinguished composer, ethno-musicologist, sound recordist, archivist, performer, dynamic and entertaining lecturer, record producer, photographer and author.’ As he was so broadly accomplished, he was involved in every aspect of the recording and archiving process of his music, which he gathered from across the world; beginning in the Middle East in 1966 and spreading through North and East African from 1969 till 1975. He later went on to record across the Pacific Ocean for ten years, from 1978. He is stated to have recorded hundreds of tribes and is commended for forming close relationships with them, which allowed him to gain permission to record their music.

Mary K. Oyer, b. 1923

Mary Oyer graduated from Goshen College – a private Christian college, historically affiliated with the Mennonite Church – in 1945, but was soon to return as she was invited to teach the General Education course integrating the study of music and visual art. She continued to teach at Goshen College, when in 1968 Oyer applied to be sent to a US Government funded program for Black Studies, operated by the faculty of UCLA. She was accepted and spent the summer of 1968 at UCLA and then travelling to five Sub-Saharan countries, from Senegal to Kenya in the summer of 1969, with a stop off in Uganda on her way home. Here she encountered Evalisto Muyinda, an out of work court musician playing at the Kampala Museum. She was taken by the endingidi, the one-stringed fiddle he was playing; she made her first recording, using her friend’s recorder, and bought an endingidi from Muyinda. [Can be found in the search under ‘Working Title: Evalisto Muyinda at the Uganda National Museum’] My favourite part about the Mary K. Oyer African Music Archive is that when searching every track, it lists the accompanying commentary from Mary Oyer, so you can hear in her own words the description of the music and the story behind it. By the end of the summer, after initially deciding between a focus on music and art, Oyer knew she wanted to channel her efforts into indigenous music. As a teacher, ‘She saw the enriching possibilities for including cross-cultural music in her related arts courses at Goshen College’ and began to teach an annual African Arts course. Over 20 years, Oyer visited 22 countries as she was lucky enough to receive funding from various projects: Kenya National Archives, Kenya Conservatoire of Music, a teaching assignment Kenyatta University and she worked with Mennonite Central Committee and Peace Corp. She was able to use her role as teacher and lecturer to spread the importance and beauty of traditional African music to young school children in Indiana, up to university students across the US and Canada. Oyer’s legacy has been continued due to a few key individuals understanding the significance of her work. Professor Debra Brubaker began the archive, Solomon Fenton-Miller began digitising the tapes and creating an outline for an archive of the information found on those recordings and Lisa Horst Schrock completed the digitisation process and interviewed Oyer about her travels and field recordings.

- All of Mary K. Oyer’s recordings can be found and listened to online in the Mary K. Oyer African Music Archive Database. You must email the Goshen College Music Department Office Coordinator (email address can be found on the website) to obtain a login and password to the database, who responded very quickly. There is a very useful Help page that makes it very easy to manoeuvre the archive. It is intended mostly for scholars, however, anyone expressing an interest will be granted access

Peter Cooke, b. 1930

Another teacher, Peter Cooke, began recording traditional African music when he began teaching at the Makerere College School in 1964. He was bereft of recordings of local music, and, at this time, only had the recordings that Hugh Tracey had made a few decades before, which were from all over Africa. When asked about the importance of recording traditional African music, he states ‘It was crucial to me to be able to direct the attention of young Ugandans to their own musical traditions: so often at weekends my wife and I drove off with students from different parts of the country to sample the music of their own local village musicians.’ An impressive example of initiative that lead one man, and his wife, to create essential recordings, in order to inspire his students. He was then transferred to run the music department in the National Teachers’ College at Kyambogo, where his recording work ‘took on even more importance.’ However, when it came to the archiving of Uganda tribal music, Cooke faced a disappointing set back; ‘It was important to leave copies of materials behind for further use by the Ugandans and others that followed me after I left [Uganda] in 1968. Unfortunately the tape copies I left behind just vanished during the chaotic years of Amin’s rule.’ He then contrasts the situation in Uganda with the ease and quality of archiving in Scotland, where he next went on to work at the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh, highlighting the imperative need for a more sustainable system for archiving in Uganda. Cooke also noted the importance of dissemination, which is why his work is produced on CDs, with teaching booklets making use of well documented recordings, complete with transcriptions and texts.

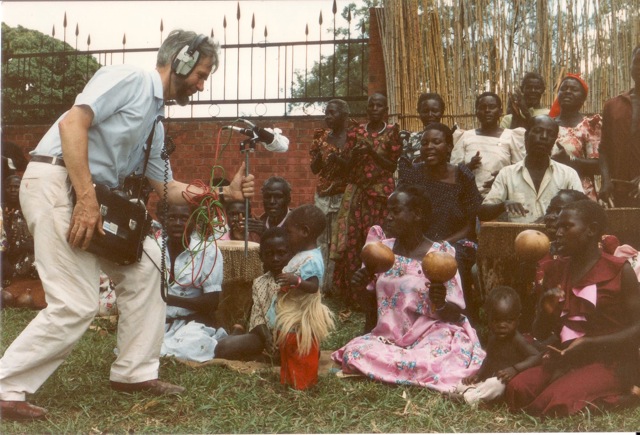

Cooke recording the Abasaasi, a team of drummers and singers outside the Kabaka’s country palace at Abamunanika in 1987 who had gathered to sing the praises of Prince Ronald Mutebi who had just returned from exile in London

However, as Cooke’s aim is, and always has been, to make traditional Ugandan music available to Ugandans, he was determined to see his work accessible there and it is now available at the Makerere University, although it wasn’t a simple decision; ‘until I was assured that a well managed archive was being set up at Makerere I was loath to deposit my materials there, after what had happened at Kyambogo Teachers’ College. The Makerere archive eventually came about through the good works of Sylvia Nannyonga Tamusuza and her Norwegian partners, though I had approached the librarian at Makerere about such a possibility many years previously.’ He has also sent his recordings back to other places in Uganda, such as to the Batwa ‘through the good offices of Chris Kidd, a post-grad at the time who was working with the Batwa’ and the family of Benedicto Mubangizi, who Cooke describes as a ‘marvellous person – teacher, educator, choir trainer, composer and folklorist’. He had made copies of this musician’s work in the 1960s and 1980s and tries ‘as much as possible to get samples back to the individual musicians’ he works with, but states ‘This is not always possible.’

When asked about how he would like to change the way his materials are archived, Cooke’s concern, firstly at the Makerere University, is that the archive is not accessible to everyone; ‘I am also very concerned to see that the Makerere recordings are made available to more than simply the university staff and students in that institution. In other words I would like to see that listening facilities are afforded to any Ugandan who want to listen to recordings at the archive. At present I don’t know what the position is.’ In addition, he hopes that ‘one of the original aims of the Makerere archive is followed through – namely to create ‘out-stations’ where further copies of the material at Makerere are made available in different areas of Uganda.’

Soga ebigwala trumpet team at Nambote village 1994

His material is also available at the British Library, which is able to be accessed by everyone online. However, it is quite a difficult archive for novices to use, and, as highlighted by Cooke, ‘Alternative names are an example:- Ebigwala, bigwara , amagwara, magwara, amagwala etc. for the Soga gourd trumpets,’ that make searching on the British Archive, regarding East African music, often a tricky task. In addition, sometimes it is difficult to know, for those who are not experts, exactly how the East African words are spelt: Cooke suggests that ‘a “fuzzy” keyword search facility seems very necessary.’ Moreover, the British Library online archive is difficult to use for Ugandans, as they often experience power cuts, do not have the necessary bandwidth to stream the content and are unable to actually download the material for study. Cooke is well aware of the short falls when it comes to the availability and accessibility of his material, and calls for the improvement of the online facilities available to those who want to share their music.

Finally, Cooke shared his thoughts on the future of archiving African Music, particularly in their country of origin. He gave frustrating examples of tapes being stored in terrible conditions, archives being so disorganised that, even with funding, it would take 20 years to archive properly and equipment being broken because it was not used according to instructions. However, there were examples that gave hope for the archiving of East African music, in Africa; ‘I visited the Ethiopian archives while stranded in Khartoum for four days (by Ethiopian Airways in 1988 I believe) and found […] local scholars, some of them trained in the UK, were doing good work with minimal resources and doing some fine fieldwork with video-cameras.’ He ends with ‘There are plenty of Ugandans who understand the value of a good archives. They need to be able to persuade their government to fund them properly. They also need to pull together.’

- Nearly all of Cooke’s material is available online at the Peter Cooke Uganda Collection, British Library

- There is an archive of his work at the Makerere University in Uganda, which must be listened to onsite. The availability of this archive to the general public is unknown to Cooke (though his concern is that it should be available to everyone)

- His personal website gives details of all published work he has done and where it can be found

- He also has copies of his recordings at the Indiana Archive, Bloomington

References

Hugh Tracey

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Tracey

http://www.ru.ac.za/ilam/history/hughtraceysportrait/

http://www.swp-records.com/Profiles/Hugh%20Tracey/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7YvnRFvSJeo&gl=NL&hl=nl

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QRjQnqjGCH0

http://www.afropop.org/wp/2295/hugh-tracey-discover-and-record/

http://www.muzikifan.com/tracey.html

Klaus Wachsmann

http://startjournal.org/2013/01/on-cultural-destiny-wachsmann-archive/

http://www.ethnomusicology.org/?Prizes_Wachsmann

http://www.musicology.ucla.edu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1279:wachsmann-klaus&catid=93&Itemid=226

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klaus_Wachsmann

S. Nannyonga-Tamusuza, T. Solomon, 2012. ‘Ethnomusicology in East Africa: Perspectives from Uganda and Beyond’. Kampala: Fountain Publishers

David Fanshawe

http://www.africansanctus.com/index.htm

http://www.fanshawe.com/index.html

Mary K. Oyer

http://www.goshen.edu/music/department-home/oyer-archive/

Peter Cooke

http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/petercooke/biography.html

With thanks to everyone I interviewed and who kindly helped with any aspect of this article.